I have been eating hemp seed in my breakfast for about a decade. It is an excellent source of protein and omega fatty acids. As a plant-eater I have regarded it as an essential source of these nutrients, since I don’t consume fishes or other sea animals. I was very pleased a year or so ago to see that one of the big-box retailers began carrying their own brand of hemp seed at a very competitive price. This has gone well for me until last week. Enter hemp seed shells

I began noticing these shells in my breakfast cereal at an alarming rate. While they are essentially harmless, they can stick to the inside of your mouth or the back of you tongue like little suction cups, and can be very annoying. I have never had to deal with them before. So each morning I would sort through my quarter cup of hemp seeds before putting them in the bowl. In the process I also discovered other odd accompaniments such as various grass seeds, and other unidentified bits of stuff.

The question is, why now? Was it just a bad day at the mill and some machine got out of adjustment? Perhaps, or is it that their supplier is having trouble keeping up with the demand, and is taking shortcuts in their processing? Or did they turn to a cheaper supplier who is less scrupulous about their product?

Finally I decided go ahead and sort all the hemp seed I had- about 3 pounds. What I found turned out to be much more alarming than I expected. [Warning: Forensic analysis of your food is not for the faint of heart- natural products inevitably carry with them bits and pieces of the natural world from which them come. Proper processing eliminates most of the undesirable stuff, but not all of it…]

As I mentioned, the shells were the original impetus for this investigation, and I do consider this to be an inferior product due to the amount of shells. But the other stuff is a different story…

It has been many years since I took a graduate course in agrostology (the study of grasses) so am not really up to identifying the grass seeds, though it is possible that some of them are Spike Oat (Avenula hookeri) or a related species. Seeds of an invasive species? Who cares if you just going to eat them. I don’t think most grass seeds pose any threat to my health. But what about those other bits?

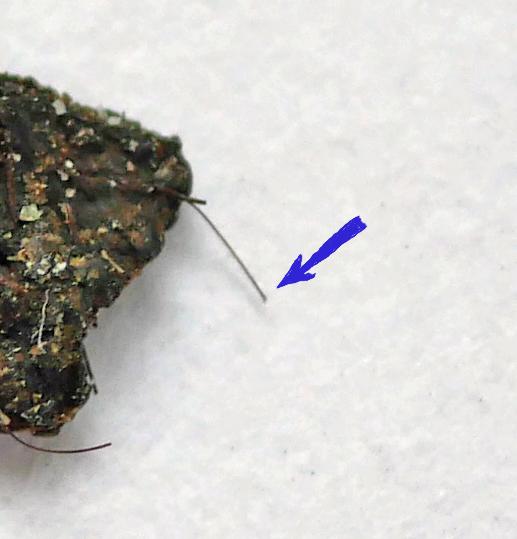

Under the microscope they look like amorphous dark material with dark-colored fibers protruding. Given their dark appearance I considered the possibility that they could be hairs of some sort, but obviously there are thousands of kinds of fibers in the world, so I withheld any opinion about that.

This particular fiber appeared to be frayed on the end, which I thought might indicate that it was manmade? (unfortunately this image is a bit out of focus, and I cannot replicate it now.)

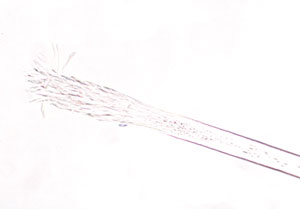

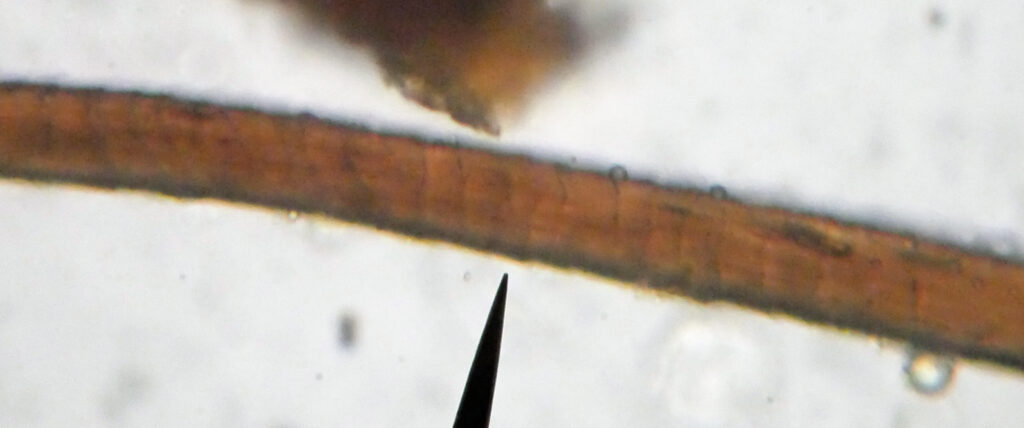

I broke the end off that fiber with tweezers and placed in on a microscope slide with a drop of water. What I saw definitely did not look manmade!

After looking through some forensic references on fiber and hair identification I began to suspect that this was indeed an animal hair. Classically, cat hairs are known to have a frayed root.

This image from the FBI report Forensic Science Communications July 2004 – Volume 6 – Number 3 Microscopy of Hair Part II: A Practical Guide and Manual for Animal Hairs shows the frayed root of a cat hair.

Cat Hair Root – Forensic Science Communications July 2004 – Volume 6 – Number 3 Microscopy of Hair Part II: A Practical Guide and Manual for Animal Hairs shows the frayed root of a cat hair

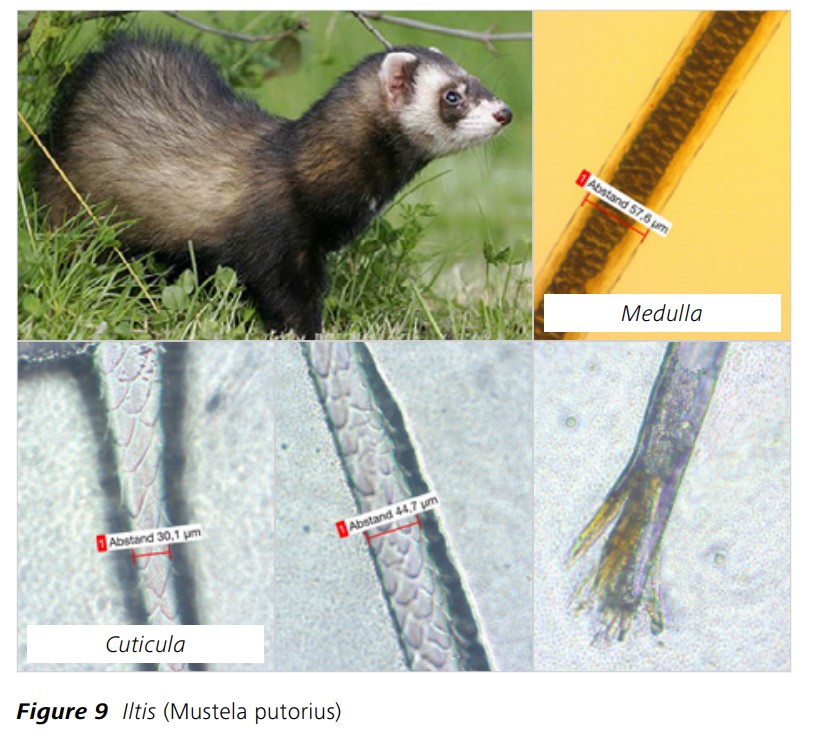

But the European Polecat looks like a better match. Since most hemp seed comes from Canada, I would assume it is not from a European Polecat, I could not find images of North American ferret hair roots, but I suspect they would be similar. A polecat in the hemp field? A barn cat?

You can decide. I still had a quarter cup of (newly-sorted) hemp seed in my breakfast this morning!

Oh yeah, and that other little black thing?

One end of it was white!

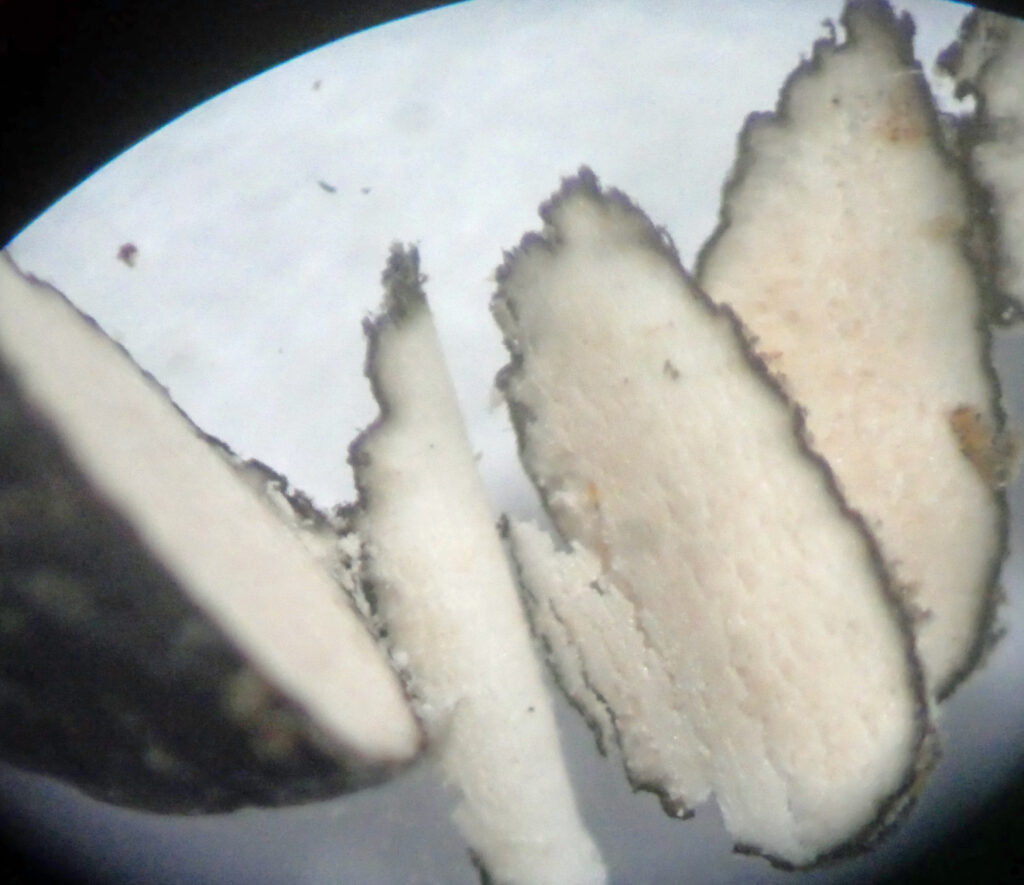

I decided to cut some sections off of the side of it, and this revealed that the entire interior was white.

Ergot is a fungus that attacks several kinds of cereal grains including rye, triticale, and less commonly wheat, barley, spelt and oats, as well as many wild grasses including Agrostis stolonifera, Alopecurus pratensis, Arrhenatherum elatius, Bromus inermis, B. secalinus, Dactylis glomerata, Festuca pratensis, F. rubra, Lolium multiflorum, L. perenne, Phalaris arundinacea, Phleum pratense. Poa pratensis and Trisetum flavescens.

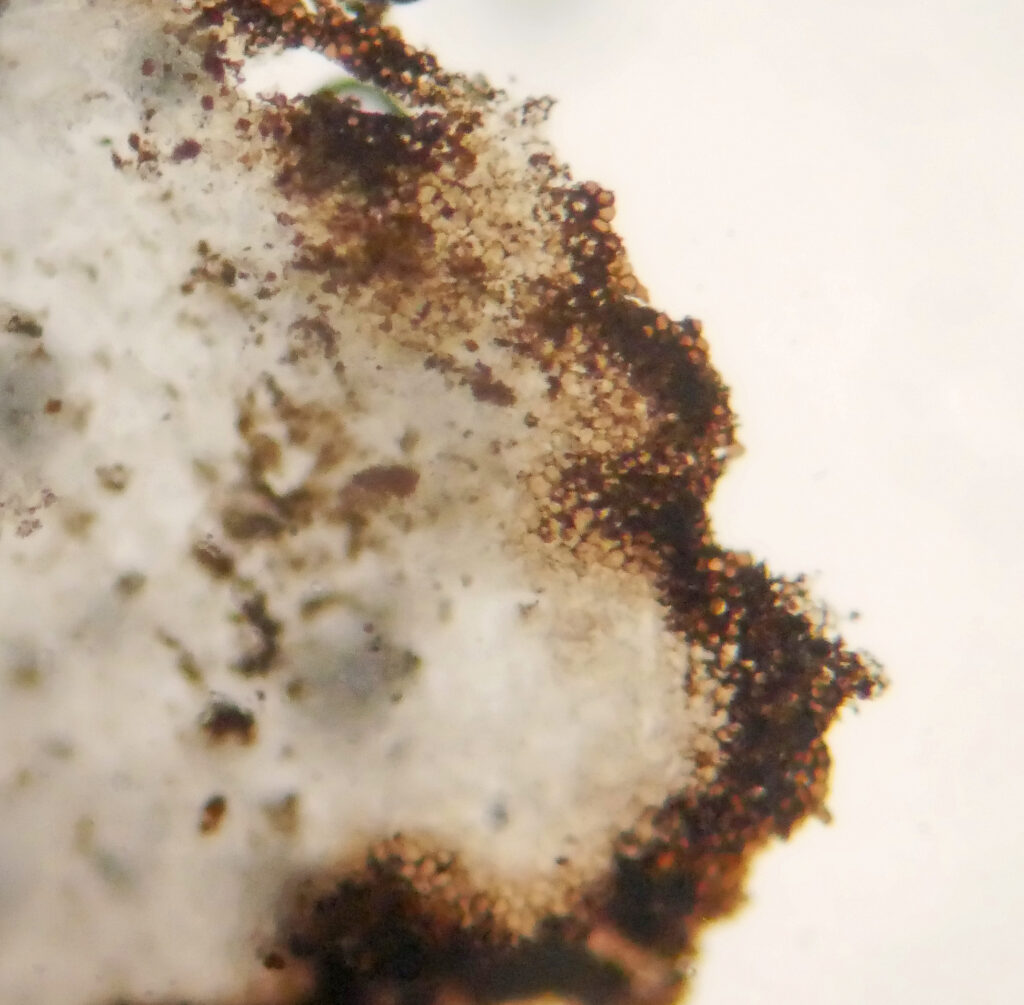

Under the microscope my sample shows a structure consistent with an ergot sclerotium. I don’t have the equipment or materials to do a proper preparation, so this is just a slice cut with a razor blade, unstained.

Here is a picture of ergot with one cut kernel showing the whitish interior.

While ergot is a toxic fungus and should not be eaten, it is very unlikely that this tiny grain, if consumed, would do any harm.

Back to this other lump:

I broke a piece off of this lump and placed it in a drop of water on a slide. I rather impatiently broke it into pieces with the tips of my tweezers. Initially I thought it would yield no interesting information, but as it rehydrated, it began to reveal new insights. There were some pieces that were obviously parts of plant stems/roots- showing characteristic vascular structures.

There were a few pieces of hair, which revealed their scaly cuticle, the nature of which can be used to identify them- though after looking at the charts in an excellent 1920 article on mammalian hairs I soon realized I didn’t care enough to pursue it.

There were several nematodes. In case you are not familiar with them, here is a description from the USDA:

“Nematodes are non-segmented worms typically 1/500 of an inch (50 µm) in diameter and 1/20 of an inch (1 mm) in length. Those few species responsible for plant diseases have received a lot of attention, but far less is known about the majority of the nematode community that plays beneficial roles in soil.

An incredible variety of nematodes function at several trophic levels of the soil food web. Some feed on the plants and algae (first trophic level); others are grazers that feed on bacteria and fungi (second trophic level); and some feed on other nematodes (higher trophic levels).”

Nematodes are everywhere in the soil, and most of us who eat lots of unprocessed plant foods probably consume quite a few of them on a regular basis. I am entirely unqualified to identify this one, but my impression is that it is a root-feeding nematode.

And then there was this:

Recent Comments